The new Silk Roads

In our second post about the Silk Roads, we look at some recent history. Today, the modern ‘Belt and Road’ plans to revive the human co-operation and intermingling of ideas and culture. The world lost this with modern transportation, wars and the concepts of modern statehood.

‘Belt and Road’ plans

This map, published by UNESCO, shows the simplest routes of what we used to call the ‘Silk Road’.

History

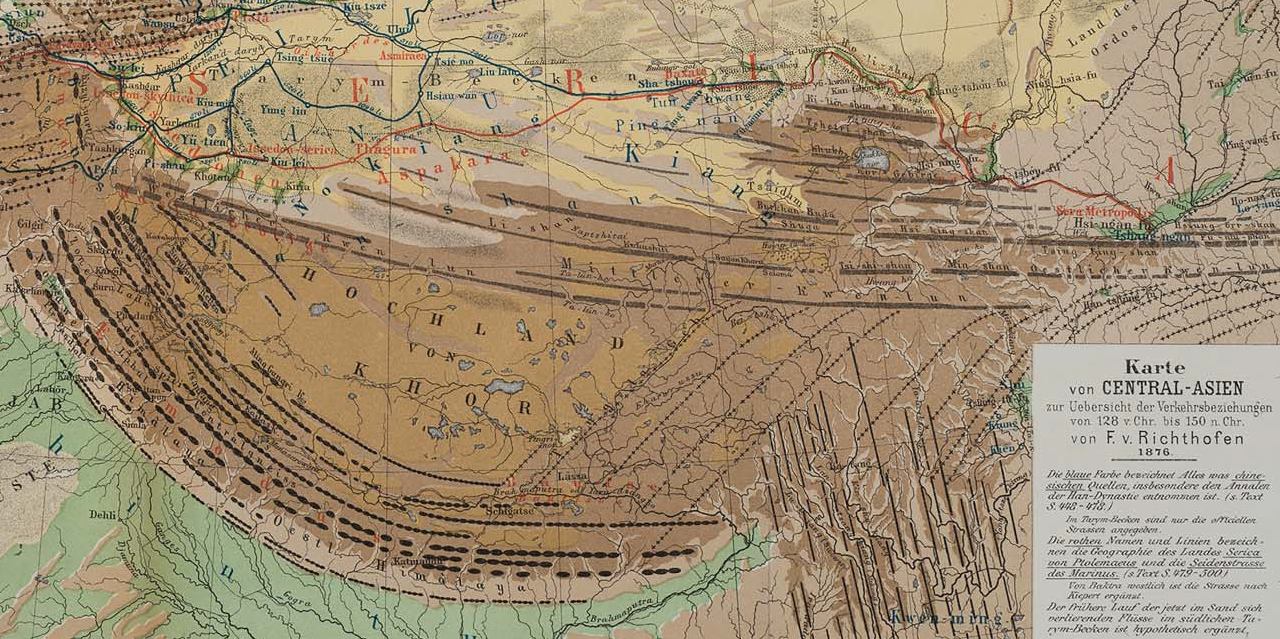

Ferdinand von Richtofen (1833-1905) first coined the term, ‘The Silk Road’, in 1876 and produced the first modern map. By then the ancient way of life of travellers and traders along the roads was almost over.

Before von Richthofen were other mapmakers. One of the earliest was geographer Ptolemy, who produced his world map, prominently showing Silk Roads, in the second century CE.

In 1988, UNESCO launched an integral study of the silk roads – the Silk Roads Dialogues – highlighting the complex cultural interactions that rose from trade along the roads.

Nowadays

Today, these ancient routes have a new purpose.

In 2013, in Kazakhstan, China’s President Xi Jinping hinted: “throughout the millennia, the people of various countries along the Silk Roads have jointly written a chapter of friendship…”. In 2017, at a ceremony in Beijing to open The Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, he formalised these thoughts:

Over 2,000 years ago, our ancestors, trekking across vast steppes and deserts, opened the transcontinental passage connecting Asia, Europe and Africa, known today as the Silk Road. Our ancestors, navigating rough seas, created sea routes linking the East with the West, the maritime Silk Road. These ancient silk routes opened windows of friendly engagement among nations, adding a splendid chapter to the history of human progress.

The ancient silk routes spanned the valleys of the Nile, the Tigris and Euphrates, the Indus and Ganges and the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers. They connected the birthplaces of the Egyptian, Babylonian, Indian and Chinese civilizations as well as the lands of Buddhism, Christianity and Islam and homes of people of different nationalities and races.

The ancient silk routes were not for trade only, they boosted flows of knowledge as well. Through these routes, Chinese silk, porcelain, lacquer work and ironware were shipped to the West, while pepper, flax, spices, grape and pomegranate entered China.

President Xi announced that China would allot billions of RMB to help build the Belt and Road initiatives (BRI). (The “belts” in the initiative refer to railroads that will connect China with Europe, Russia, the Middle East and Central and Southeast Asia. The “roads” refer to maritime routes and multiple ports that will be enhanced or built along the South China Sea, Indian Ocean and South Pacific.)

Today, three years later, more than sixty countries — with two-thirds of the world’s population — have signed on to projects or indicated an interest in doing so. China has already spent an estimated US$200 billion on such projects. Some have predicted that China’s expense over the BRI could reach US$1.2–1.3 trillion by 2027.

Some analysts see the project as yet another extension of China’s rising power. The United States has concern that the BRI could be a Trojan horse for China-led regional development and military expansion. Washington has raised alarm over Beijing’s actions, but it has struggled to offer governments in the region a more appealing economic vision.

However, a recent important study from Chatham House, the British think tank, the authors see no threats from BRI:

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is frequently portrayed as a geopolitical strategy that ensnares countries in unsustainable debt and allows China undue influence. However, the available evidence challenges this position: economic factors are the primary driver of current BRI projects.

In Sri Lanka and Malaysia, the two most widely cited ‘victims’ of China’s ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ the most controversial BRI projects were initiated by the recipient governments, which pursued their own domestic agendas. Their debt problems arose mainly from the misconduct of local elites and Western-dominated financial markets.

The authors believe that some of the initial projects were poorly conceived and planned. Recipient governments should take more responsibility to examine the viability and sustainability of the projects they undertake.

Tellingly though:

Policymakers in non-BRI states should: avoid treating the fragmented activities of the BRI as if they were being strategically directed from the top down; provide alternative development financing options to recipient states; engage recipients and China to improve BRI governance; and help improve the transparency of ‘megaprojects’.

The Silk Roads have formed a vital part in the history of the world for centuries. The ideas and exchange of cultures that have taken place have enriched society. The trade that passed each way between countries and cities along the routes has become part of everyday life in many countries. As it develops, the Belt and Road initiative will achieve the same goals.

However, progress has slowed recently, largely because of the COVID-19 epidemic. We shall explore this and other constraints in a future post.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang