Who do you think you are?

I receive emails from interesting thinkers all over the world. Often their topics coincide – or I find ways in which they do. Three such articles came my way this week. They made me think. I hope I make you think too.

Identity

In no special order, the first is here. Roger Darlington writes about the question of ‘identity’. He asks interesting questions about identity and how we assess ours. And he successfully contrasts how simple the question of our personal identity used to be, with how much more complex it is today.

Democracy

The second article is here. Here, the author reviews the life and thought of Albert Hirschman, a passionate democratic thinker with a wide following. Of interest to me are Hirschman’s views on social change.

The second aspect of Hirschman’s work is his preoccupation with ways to reinforce democracy. “Revolutionary stances are not simply antidemocratic but also simplistic and ineffective,” Hirschman maintains. In other words, it is democratic for individuals to protest but, once they become part of a ‘movement’, it will inevitably become undemocratic.

Culture

The third article is by Christy Wampole, an essayist and professor at Princeton University. She discusses ‘cultural degeneration’. She describes a perceived decline in the standards of popular artistic culture. However, she concludes:

Crowds

Finally, I refer to our own post of a year ago. The above writers, at some point, all describe group behaviour. Our ‘Identity’ mostly depends on being part of a group. ‘Revolutions’ are the products of crowds. ‘Culture’, in both the artistic and national sense, is a form of crowd behaviour. We think and behave differently when we feel ourselves to be part of a crowd. We do things we otherwise might not do. We enthusiastically set aside our individuality for the ‘buzz’ of unity with others. This is dangerous – for everyone – and in many ways.

Our tribal species

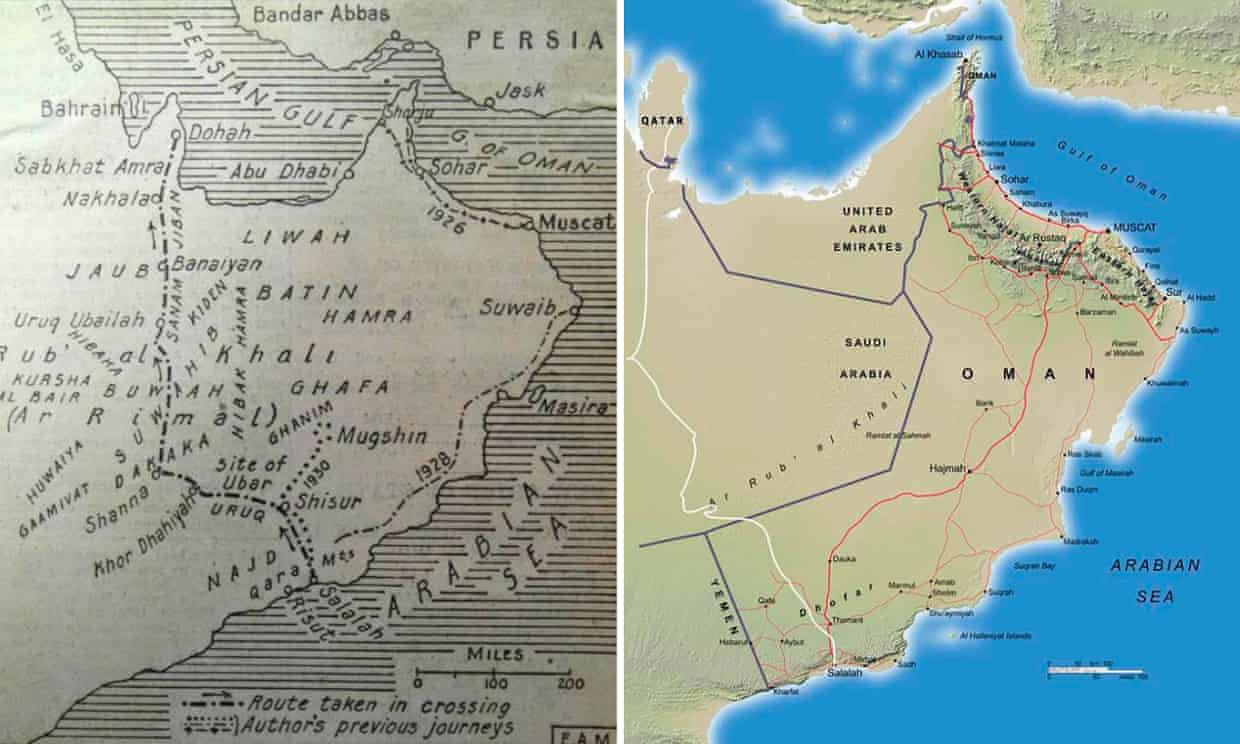

Yet, humans are tribal. Survival depended on trust and co-operation between members of the tribe. Beliefs and social norms emerged within each tribe. Different tribes had different beliefs. When tribes competed for resources, fights broke out. Bertram Thomas describes this vividly in his amazing ‘Arabia Felix’. In 1932, this British civil servant walked across the ‘empty quarter’, or Rub al-Khali, the world’s largest sand desert, in the south of the Arabian peninsula.

On the left is Thomas’ map. On the right is the journey made by explorer Mark Evans, who replicated Thomas’ journey in 2016

Thomas’ book is fascinating. Of particular interest for me are the semi-nomadic family tribes he came across in this ‘empty’ desert. Often not more than 40 people, each family had different customs and beliefs. If one family approached an oasis, they needed to creep up carefully to see if another family was already guarding it. ‘Other families’ were usually enemies. These conditions existed within one relatively compact region only 90 years ago.

Some might look at the region today and identify Saudi-Arabia, or Oman or Qatar (nations only created since the first world war) and visualise people living there as homogeneous groups of citizens with shared values and beliefs. In the 1930’s they were not at all homogeneous, as Thomas relates. Today also, the people are not homogeneous. The tribes are larger, perhaps, and less isolated, but they are still tribes – in reality if not in name.

Little has changed

This is how human society used to be, one might think. Today it is different – isn’t it? French people live in France and have a French culture. British people have the British culture, Indians in India and so on.

Yet, in 2018, India identified 19,500 mother tongues among its 1.36 billion inhabitants. Among the Philippines’ 85 million people, over 120 languages are mother tongues. Even in supposedly monolingual China, linguists believe there are over 300 languages. President de Gaulle famously decreed in the 1958 French Constitution that everyone in France should speak French; yet there are still 75 recognised regional French languages today.

With language comes culture, the sense of identity, values and beliefs. We may think the human race has changed but, in these fundamental ways, it is much the same as it has always been.

And yet, our world today is completely different.

Today’s world

Anyone alive today is witnessing changes more profound and far-reaching than any changes in human history. We are at the start of developments that have so far belonged only to science fiction. Of all the images that depict this, none is more powerful than the first photograph taken of the earth from space in 1972. (One can see clearly at the top of this photograph, the ‘empty quarter’ over which Thomas walked 40 years earlier!)

In 1972, on our small sphere, lived 3.8 billion people. 7.8 billion live in the same space today. In 1972, airlines carried around 331 million passengers. Pre-COVID passengers in 2020 were forecast to be 4.7 billion. In 2020 272 million people migrated. Between 1960 and 2000 46.5 million people became refugees. In 2018 alone, nearly 75 million people sought refuge outside the country in which they were born.

My purpose is not to highlight the supposed self-indulgence of air passengers or the tragedies of refugees. But, if half the world’s population are traveling to other countries each year and possibly 10% are permanently moving home, tribal identities are quickly becoming blurred.

None of this is new. From the Hittites to the Romans, the Mongols to the Colonists, the Aztecs and the Vikings, entire cultures have been obliterated or absorbed by others. But three aspects today are unprecedented. First, these are global trends that are increasing. Second, we all know about them, courtesy of the Internet. Thirdly, in the 1970’s probably less than 30 million students went to university.

By 2030, the OECD expects over 300 million people around the world to graduate. Even in the most developed countries, full-time education rarely continued beyond age 14 in the 70’s. Today, compulsory education is generally until 16 or older.

Population movement, globalised news and vastly increased education – what an astonishing transformation in a mere 70 years! And this is just the beginning…

We need a new approach

Disturbingly however, as our three authors point out, our political and social systems are no longer adequate, even at the start of this transformation of humanity. Tribal identity is still vital to most people. National pride is actively encouraged by politicians. Democracy fails whenever individual views are ignored or when only populism determines how a country is to be governed. Art and culture are stifled by ‘conventional wisdom’ and ‘good taste’. Freedom of the press is non-existent when ‘popular opinion’ leads to self-censorship. (Try publishing a pro-China article today in any western journal, for example!)

So – what is to be done?

It would be irrational to expect the human need to identify with a tribe to disappear. Psychologists tell us, in any case, that individuals need to identify with a group for their mental health. Furthermore, one could believe that, as globalisation continues, our behaviours and political systems will adjust, as they have before. Current western democratic systems urgently need radical overhaul, as Dambisa Moyo suggests in her brilliant book ‘Edge of Chaos’. That is a huge debate that needs to take place very soon – but not here.

Meanwhile being aware of the global changes taking place is vital. We should encourage and accept different opinions, even on popular issues. International travel needs expanding, not reducing. Immigration is good for everyone. Refugees are welcome. Only by knowing each other better will we understand better. Tribal dogmas belong to the past.

We know now that we are all citizens of Earth. May peace be with us.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang