EMPIRE

Was the British Empire a ‘good thing’? Does it matter now, anyway?

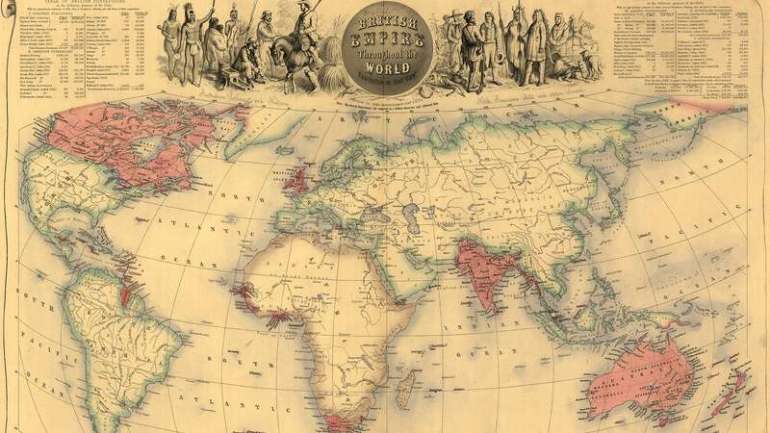

A few years before I was born, the British Empire occupied the largest land area in its history. It covered roughly one-quarter of the world. It was the largest Empire the world has so far known. My Mother was born in Bangalore, India. Her Father owned coffee plantations in Mysore. I have lived most of my working life in one of the last British Colonies. You might think that I cannot be objective about the British Empire. But you would be wrong.

Almost every month, it seems, a new book appears about the Empire. British people once saw it as a relatively benevolent, progressive force in the world. Most writers of any culture now critically portray its racism, violence, and undemocratic institutions. Its defenders still exist but, because the Empire was so vast and endured for so long, it is possible to pick out incidents and trends to support almost any viewpoint.

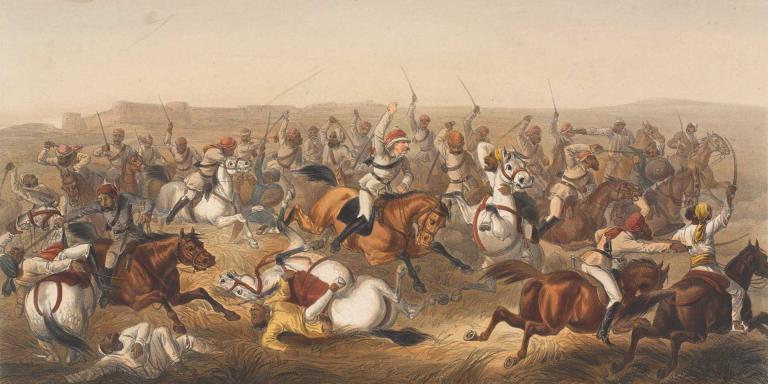

An event is tragic or heroic depending on which side one sits. Was the ‘Indian Mutiny’ engineered by traitorous Indian soldiers who slaughtered innocent British families? Or was it the first ‘Indian Independence’ movement in which brave, subjugated, citizens exercised their civil rights to protest evil British colonialism? Was the Amritsar massacre a tough, necessary, response by British troops to a dangerous riot? Or was it an appalling slaughter of civilians that defined the very nature of unrestrained, brutal, colonial military power?

Slavery

I was reminded of these ambivalences by Padraic Scanlan’s recent article in Aeon – The Emancipated Empire. Padraic Scanlan is an assistant professor at the Centre for Industrial Relations and Human Resources at the University of Toronto. He is also a research associate at the Centre for History and Economics at Harvard University and the University of Cambridge. The tagline of his article reads:

He then goes on, eloquently, to chart the history of the abolition movement in the UK.

Padraic Scanlan’s tagline is, however, wrong. The British Empire was never ‘built’. It was a disjointed, opportunistic, series of private ventures, which owed little to any British Government of the time. The first permanent colony (Jamestown in Virginia) began partly, ironically, as a flight to freedom from repression in Britain.

As Niall Ferguson, the eminent historian, writes in his recently updated ‘Empire – `How Britain Made the Modern World’, “It should never be forgotten that…the British Empire was not conceived by a group of self-conscious imperialists aiming to establish English rule over foreign lands…The British Empire started out using enterprising freelancers as much as official forces.”

And yes, of course, the slave trade became a core rationale of the Empire – profits for British entrepreneurs. Between 1662 and 1807, nearly three and a half million Africans were transported to the New World – three times the number of white immigrants in the same period. The British Parliament finally ended slavery on 1 August 1834. To help gain support for the anti-slavery bill, £20 million (40% of the national budget) was set aside to compensate British slave owners.

The British were not the first race to possess slaves or to buy and sell human beings. Almost every country at some time has done so. Some still do. In 2019, the Guardian newspaper estimated that 40.3 million people (three times the number ever involved in the slave trade) are slaves today. It is wrong, therefore, to think of the British Empire solely in terms of the evils of slavery. A balanced view includes the benefits of the Empire as well as other, less obvious, defects.

Positives

In 2003, Niall Ferguson wrote:

In the updated preface of my edition in 2018 he writes:

Niall Ferguson asks us to read his book carefully and to engage with his arguments and the evidence he presents. After stringent attacks from many historians, he persists in his belief that the British Empire was, overall, a global force for good.

My view

Well, sir, I have read your book carefully and have learned a lot from your arguments and the evidence you provide. I agree that Britain ‘made’ the modern world. But I am not sure if that was a good thing.

Firstly, as the first President of the PRC, Zhou Enlai, supposedly said about the effects of the French Revolution (in 1789): ‘It’s too early to tell.’ Britain’s last significant colony, Hong Kong, ceased being British territory only 24 years ago. Most of the Empire’s other territories became independent only in the last seventy years. The Empire has barely fallen. Making a judgement of any kind, critical or supportive, is surely premature.

Secondly, in these days of environmental concerns, what about the impact of the Industrial Revolution, that started in Britain? Coal, the railways, oil, factories, vehicles, and the paraphernalia of wealth creation all began as triumphal exports of British imperialism. To be sure, better health, much of it enabled by the Empire, brought enormous benefits to millions. But the world now contains over three times as many people as it did when the Empire was at its height. One could argue that the British Empire was not wholly responsible for all this. One could also argue that, even if the British had not been so successful, other colonial powers would have done the same; they might have been worse.

Thirdly however, and most important in my view, is the way in which the British Empire imposed its values on others. The ‘Western World’ (the Anglo-Saxon world that is) continues to impose them to this day. In my post of June 2020, ‘Modern Missionaries’, I refer to the way in which the West has decided what ‘human rights’ should be, for example. If others do not believe in them, they are heathen, barbarians, criminals even. Jan Morris in her seminal three-volume history of the British Empire, ‘Pax Britannica’, refers to the patronising attitudes of British colonial officials towards ‘the natives.’ ‘We are here to look after you, until you are able to look after yourselves’. In other words, ‘our way is better than yours, but if you behave, we’ll help you catch up to our standards.’

Personal experience

It was thus in Hong Kong until the later 1980’s. Every senior Government official was from Britain. Senior management in almost all international companies were Anglo-Saxons. Training schemes for Chinese graduates, where they existed, enabled them to progress to junior management roles only after seven years or more. The better organisations realised they should do more. ‘We’ll promote them when they are ready,’ was the mantra. ‘Being ready’ most often meant behaving in ‘our way, with our values’, more than grasping the technical aspects of management.

This pervasive culture showed itself in other ways. In the 1970’s and 1980’s being an expatriate was rewarding. Companies provided housing, schooling, travel, and other benefits as well as generous salaries. This was to entice skilled and experienced executives to work in sometimes difficult or dangerous locations. These expatriates originated from Anglo-Saxon countries. However, they were soon joined by ‘Third Country Nationals’, an odious phrase to describe expatriates of the same level from other countries, usually Asia. They received packages that cost companies significantly less. Executives in those days received remuneration based on their country of origin, not their job level, education, skills, or experience. White, Anglo-Saxon, expatriates were at the top, Asian expatriates came next. Locals of course came last. (I confess that I was part of this system for a few years and benefitted personally from it. In fairness also, I was instrumental in bringing it to an end in the organisations for which I had some responsibility.)

It matters

This is, arguably, the most important legacy of the British Empire. Arguably, it will last longer than all the others. It resonates with the nature of those who believe that their tribe, their culture, are superior to all others. And this is most of us. It just so happened that Britain had the most powerful ways to coerce others for a few hundred years.

Does it matter? It is tempting to say: ‘not really. It all happened long ago. We have moved on and cannot worry about the actions of our predecessors.’ Should the Normans apologise for invading England? How about the Mongols for terrorising half the known world? What did the Romans ever do for us?

All conquerors are superior beings (or they would not have conquered). They all leave something of their culture behind. That is inevitable. However, when empires fall and foreign armies depart, the conquered then choose what to retain and what to reject of their conquerors’ philosophies.

However, the British Empire (a.k.a. the Western World) still tries to impose its values on others. The Empire may have gone but its legacy, cultural imperialism, will trouble the world for a long time.

This is what matters.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang